Module 2: Essentials

Scala expressions, types and values

In functional programming an expression is a unit of code that returns a value after executed. Expressions make a foundation of functional programming since they allow to return data instead of modifying existing data.

An expression is as simple as:

"hello world"

1 + 1

5 < 3

Variables

In this context, we can define a variable as the result of an expression. In Scala, you can define variables in three basic ways. We will further view in detail its differences and usages, but for now lets settle with only learning how to define them:

val

The usage of val is as follows: val name: type = value

For example:

val number: Int = 5

val word: String = "Hi!"

val something = 45.6

A variable defined with val cannot change value, the type annotation is optional, but

type will be inferred.

var

The usage of var is the following: var name: type = value

For example :

var variable = 8

variable = 15

variable = 36

As val, type annotation is optional and type will be inferred, but for this case, the value is

variable. Type should be preserved, this means you cannot define a var as a Double

and then use it as a string. In order to follow functional paradigm val should

be preferred over var.

def

We can use def as follows: def name: type = value

For example

def number: Int = 15 + 5

def word = "Weird"

def print = println("")

When defining values, def works pretty much as var/val (except for some details that will be further

addressed), the great difference comes from the fact that def will not only store the

final result of the expression, but the whole expression. Also, as we are going to see

in detail next, it can be used to define functions.

Expression blocks

You can have a set of expressions surrounded by { }, these groups are called

expression blocks and can be composed of any of the expressions previously mentioned.

For example:

{

val a = 5

val b = 6

println(a)

println(b)

}

Functions

A function is an expression that takes parameters. Parameters need to specify type and can be as many as needed.

It is used in the following way:

(param1: type, param2: type, ..., paramN: type) => block expression (function body)

For example:

(x: Int, y: Int, z:Int) => (x + y)*z

(a: Int) => {

println("hello human")

a*100

}

As we previously anticipated, def can be used to define functions as var/val,

type annotation is optional and type will be inferred.

def name(param1: type, param2: type, ..., paramN: type): return_type = block expression (function body)

Some examples are:

def product(x: Int, y: Int, z:Int) = (x + y)*z

def sameResultAlways(a: Int, b: Double): Boolean =

{

println("I don't care about your input")

true

}

In further modules we will talk more about functions, for now you know how to define them.

Boolean expressions

In Scala as in most languages we have the standard boolean expressions:

Constant

true

false

Negation

val a: Boolean

!a

Conjunctions and disjuntions

val a: Boolean

val b: Boolean

a && b

a || b

Comparisons

a < b

a <= b

a > b

a >= b

a == b

a != b

Conditionals

We can build conditional expressions by using a boolean expression and an expression block.

if (boolean expresion) expression block

For example:

if (a > b) {

println("calculating percentage")

b/a*100

}

We can also use else statement, as usual

if (boolean expresion) expression block

else expression block

For example:

if (a > b) {

println("calculating percentage")

b/a*100

}

else {

println("calculating percentage")

a/b*100

}

Types

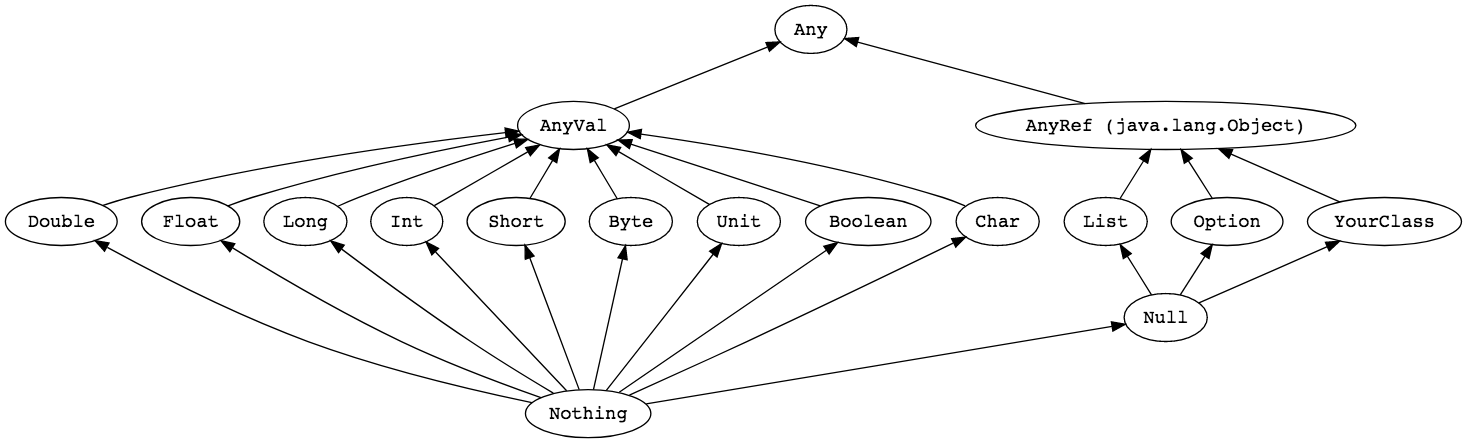

Scala is a statically typed with type inference language. This means all variables and functions have a specific type, but you don’t need to always annotate the type. This makes types a big deal in Scala. As we have previously reviewed, all variables have an assigned type that will not change, as well as functions and function’s parameters. The basic Scala types are illustrated on the following picture:

As we can see they all come from a mother type called Any and then divide into two families: AnyVal and AnyRef. AnyVal types are common to every programmer, but AnyRef family might not be so, we are going to elaborate a little on this.

AnyRef

AnyRef types should take parameters, this means that an AnyRef type cannot be defined on its own. This is, you can only have a list of some type, you cannot have a list of anything. For example:

val height: List[Double] = List(1.70, 1.77, 1.52, 1.92)

val middleName: List[Option[String]] = List(Option("Carlos"), None, Option("Guadalupe"))

val probabilityOfExplotion: MyVerySpecialType[Boolean] = MyVerySpecialType(true)

Evaluation Strategies

call-by-value and call-by-name

The first important thing we need to know is that no matter the evaluation strategy used it will reduce to the same value as long as we only have pure functions and the evaluation terminates.

When evaluating by call-by-value (cbv) we first evaluate the arguments of the function and then we substitute on the body of the function.

When evaluating by call-by-name (cbn) we first substitute on the body of the function the arguments as they are.

Call-by-name has the advantage that a function argument is not evaluated if the corresponding parameter is not used in the body. But sometimes it can end up evaluating the same expression multiple times.

In Scala the “standard” is cbv,

but we can use cbn to evaluate a parameter if we use : => in the definition instead of : simply.

This means:

//This function will be evaluated as cbv, since x and y are defined with : only

def sum(x: Int, y: Int): Int = x + y

//x parameter will be evaluated as cbn, since it is defined with : =>

def sum_1(x: => Int, y: Int): Int = x + y

//both parameter will be evaluated as cbn, since both x and y are defined with : =>

def sum_2(x: => Int, y: => Int): Int = x + y

This way, evaluating sum, sum_1 and sum_2 with the same parameters will result on different number of steps, but same result. This is:

sum(3*2+5, 2+3)

sum(6+5, 2+3)

sum(11, 2+3)

sum(11,5) = 11 + 5 = 16

for sum_1:

sum_1(3*2+5,2+3)

sum_1(3*2+5,5) = (3*2+5)+5 = (6 + 5) + 5 = 11 + 5 = 16

for sum_2:

sum_2(3*2+5, 2+3) = (3*2+5)+(2+3) = (6+5)+(2+3) = 11 + (2+3) = 11 + 5 = 16

Finally, as we previously mentioned, using val and def to define a value can seem to be

exactly the same. But now we can understand the difference. When we use val, we are using

a cbv evaluation to define such value. On the other hand, when we use def, we are using

cbn evaluation. For example in:

val a: Int = 1+2+3+4+5+6

val b: Int = 1+2+3+4+5+6

The variable a will be carrying the value 15 while b will be carrying the value 1+2+3+4+5+6, that will eventually evaluate to 15 anyway.

Understanding the JVM: Basics of Scala interoperability

The JVM has two main proposes:

- Allowing any program to run in every device or operating system.

- Managing and optimizing memory usage.

Scala is built on top of the JVM, which makes it a JVM language. A JVM language is any language with functionality that can be expressed in terms of a valid class filed that can be hosted on de JVM, some examples of such languages are:

- Kotlin

- Groovy

- Clojure

- Scala

The main advantage Scala has as JVM language is the interoperability with Java and some other JVM languages. In particular the interaction with the mainstream object-oriented Java programming language is straight forward.

Some of the most simple examples of Java/Scala interoperability are related to collections. Java and Scala have both very rich collections library, we can pass back and forth between Java and Scala for the following collection types:

Iterator <=> java.util.Iterator

Iterator <=> java.util.Enumeration

Iterable <=> java.lang.Iterable

Iterable <=> java.util.Collection

mutable.Buffer <=> java.util.List

mutable.Set <=> java.util.Set

mutable.Map <=> java.util.Map

mutable.ConcurrentMap <=> java.util.concurrent.ConcurrentMap

For example, we can declare a java List in scala and then convert it to a Scala Buffer:

import collection.JavaConverters._

import collection.mutable._

val jul: java.util.List[Int] = ArrayBuffer(1, 2, 3).asJava

val buf: Seq[Int] = jul.asScala

The whole JavaConverters object has many methods to interoperate between the two languages.

In general we can say you can always use existing Java code in Scala, but using Scala features without analogues on Java in Java can get tricky, but not impossible. Specially since Scala 2.12 release that takes advantage of the features included in Java 8. Some examples are:

- Traits compile directly to an inteface.

- New lambda syntax for SAM types.

- Improved type inference.

Consulting existing libraries Scaladocs and how to produce your own

As in every modern language libraries play a major roll in Scala. The usage of

SBT as build tool, simplifies

the integration of libraries, since the build.sbt file of the project will handle

the dependencies needed by simply

adding one or a few lines.

The exact commands that need to be added to your build.sbt file will generally be shown in the

readme of the library you are consulting.

For example to install the popular library ScalaTest

you only need to add:

libraryDependencies += "org.scalactic" %% "scalactic" % "3.0.5"

libraryDependencies += "org.scalatest" %% "scalatest" % "3.0.5" % "test"

resolvers += "Artima Maven Repository" at "http://repo.artima.com/releases"

addSbtPlugin("com.artima.supersafe" % "sbtplugin" % "1.1.3")

The first line installs Scalactic, ScalaTest’s sister library focused on quality through types,

from the org.scalatic repository on release 3.0.5.

The second line will Scalatest from org.scalatest on release 3.0.5.

The final two lines will install a plugin, the first specifies the repository the plugin lives in

and the second one will handle about the plugin itself.

Once installed we should only import it in the desired project as:

import org.scalatest._

In this case the _ works as * sign in java.

As we can see, installing and using a library is pretty straight forward, now it’s time to talk about how we can decide if a library contains what we need and how we should use it. In aid to this issue it exists a model to document Scala code called Scaladoc.

Scaladoc

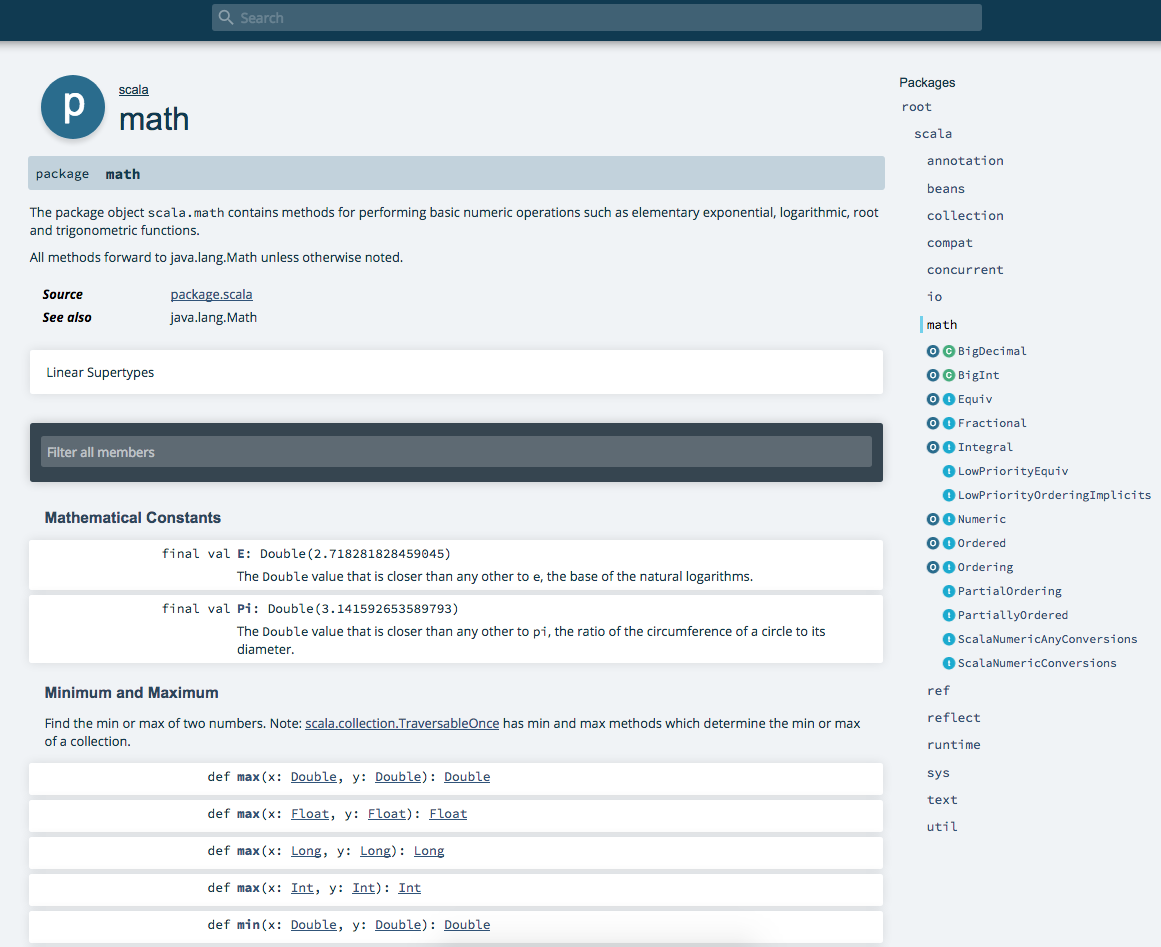

Scaladoc is based on Javadoc, and as Javadoc it works by using comments directly before the items that are going to be commented. It should be used in all packages, classes, traits, methods, and other members and the result of a good documentation is such as the one on the following picture:

The official Scaladoc for Scala is in the following page www.scala-lang.org/api/current/ the documentation is sorted by packages. Specific classes can be sorted by name by using the top bar on the page.

Once you are browsing a package you will find the following window:

On the center of the screen there are a list of methods with its description. On the right side of the screen you will find a list with a (t) symbol, (o) symbol or (c) symbol these will take you straight to the trait, object (or companion object) or class.

Navigating through scaladoc will require experience and time, you can follow the advises on the last section of the first chapter of “Scala for the impatient”, which can be downloaded for free. You can also check some features of Scaladoc on the official Scala page.

Documenting your work

As we previously saw, a good documentation translates in an easy understanding on when to use and how to use libraries of packages. So now lets focus on how to document our work. We are going to use Scaladoc style guide.

Scaladoc comments should start with /** and end with */. An advantage of Scaladoc over Javadoc

is that the format of the rest of the comments is flexible between * in the second or third row

or the whole comment in the same line, this means:

/**

*

*

* /

and

/**

*

*

*

*/

and

/** The whole comment */

Are valid. Most editors with a Scala plugin will automatically fill a template for Scaladoc once

/** is typed.

In general a good Scaladoc should contain a quick summary of the function, at the beginning. A more complex description of the subject documented can go next. Finally a group of tags, should close the documentation of the subject, which can be:

@constructor@return@throws@param@tparam@see@note@example@usecase

Among some others. For example we can document the functions we created previously:

/** This function multiplies the addition of two numbers

*

* @param x term1

* @param y term2

* @param z multiplier

* @return (x + y)*z

*/

def product(x: Int, y: Int, z:Int) = (x + y)*z

/** This function always returns true and mocks about you

*

* @param a a non important Int

* @param b a non important Double

* @return true

*/

def sameResultAlways(a: Int, b: Double): Boolean = {

println("I don't care about your input")

true

}

Once you have documented your project, you can automatically generate developer documentation by either using the scaladoc command or a SBT task.

The scaladoc command usage is the following:

$ scaladoc YourFile.scala

This will generate a root index.html file and other related files for your API documentation.

On the other hand, running the command:

$ sbt doc

Will generate the same API documentation and will place it under the target directory of your SBT project. Specifically it will be located at target/scala-2.X/api/index.html.